Uber Is Relying Heavily On Behavioral Science To Make Better Drivers

If possible, it feels like Uber is taking over the world and jumping the shark at the same time. The company has become ubiquitous in its own right. Other companies refer to their own business plan as, “We’re the Uber of….”. Fill in the blank with any number of concepts.

Uber is not without their challenges. Discussing their strategies can be a very polarizing thing. Recently, my friend Jeanne brought up the subject on Le Chic Geek. Another friend of mine brought it up on her blog and got absolutely lambasted by people. I mean, some of the worst things I’ve seen written on a public blog about women. In comparison, I got relatively little grief for covering the subject myself, but still got lectured a bit.

Amidst all that, I’m still taking the plunge into the subject of Uber drivers again. There was a really interesting NY Times article I read Sunday night. I meant to publish it yesterday but I had my Hyatt Globalist status giveaway and the day got away from me (note, if you haven’t entered yet, it’s free and you can win a year of the best hotel elite status).

It’s a long article, but there are a few key concepts and interactive games that made it a quality read:

“It was all day long, every day — texts, emails, pop-ups: ‘Hey, the morning rush has started. Get to this area, that’s where demand is biggest,’” said Ed Frantzen, a veteran Uber driver in the Chicago area. “It was always, constantly, trying to get you into a certain direction.”

Some local managers who were men went so far as to adopt a female persona for texting drivers, having found that the uptake was higher when they did.

“‘Laura’ would tell drivers: ‘Hey, the concert’s about to let out. You should head over there,’” said John P. Parker, a manager in Uber’s Dallas office in 2014 and 2015, referring to one of the personas. “We have an overwhelmingly male driver population.”

Uber acknowledged that it had experimented with female personas to increase engagement with drivers.

Uber’s goal is to have many drivers on the road to serve demand quickly. The article also points out that Uber doesn’t really like “surge pricing” in that it can reduce demand. I’m not 100% sure where the line is between regular pricing and surge pricing for Uber from a profit standpoint. But, I’m sure they’ve studied the mountains of data they’ve compiled on the subject.

The article goes on to talk about how Uber is using a tactic common to Netflix. Call it “binge driving” instead of “binge-watching”. Uber assigns the next ride to a driver before they finish their current one, targeting the area where they’ll end up. This keeps drivers busy but created an unforeseen problem:

Uber officials say the feature initially produced so many rides at times that drivers began to experience a chronic Netflix ailment — the inability to stop for a bathroom break. Amid the uproar, Uber introduced a pause button.

“Drivers were saying: ‘I can never go offline. I’m on just continuous trips. This is a problem.’ So we redesigned it,” said Maya Choksi, a senior Uber official in charge of building products that help drivers. “In the middle of the trip, you can say, ‘Stop giving me requests.’ So you can have more control over when you want to stop driving.”

It is true that drivers can pause the services’ automatic queuing feature if they need to refill their tanks, or empty them, as the case may be. Yet once they log back in and accept their next ride, the feature kicks in again. To disable it, they would have to pause it every time they picked up a new passenger. By contrast, even Netflix allows users to permanently turn off its automatic queuing feature, known as Post-Play.

Is Uber The Only One Trying To Gamify Their Drivers?

Nope. Lyft is trying to do so as well. A few years ago, Lyft was trying to find ways to encourage drivers to be on the road at peak times. That helps the drivers make more money (and Uber as well). They tried the positive approach, telling one group of drivers they could make more money if they adjusted their work schedule to drive on a different date and time. They also tried the opposite. Guess which one worked better:

For another group, Lyft reversed the calculation, displaying how much drivers were losing by sticking with Tuesdays.

The latter had a more significant effect on increasing the hours drivers scheduled during busy periods.

Kristen Berman, one of the consultants, explained at a presentation in 2014 that the experiment had roots in the field of behavioral economics, which studies the cognitive hang-ups that frequently skew decision-making. Its central finding derived from a concept known as loss aversion, which holds that people “dislike losing more than they like gaining,” Ms. Berman said.

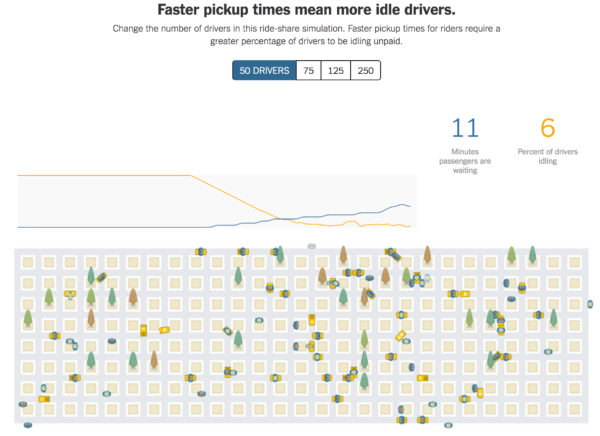

What I found equally interesting about the article was how the New York Times incorporated some min-games into the online version of the article. Obviously, this is the extension of news on the web, something you could never do with a printed newspaper.

The Final Two Pennies

It’s not terribly surprising Uber is using mind control behavioral science to better position their drivers. With the amount of money they’ve raised from investment groups, there are probably plenty of projects aimed to leverage Uber’s vast driver network to produce more revenue for the company.

I often wonder when companies like this will ultimately have to face the fact that they need to be profitable on a consistent basis. Given what I do for a living (research and invest in startups) I see plenty of companies never make it to profitability.

Uber and Lyft have both been growing at an incredible pace. Tons of money continues to fuel their growth. The New York Times combines technology and detailed research to deliver a great synopsis on the state of the ride-sharing world.

The post Uber Is Relying Heavily On Behavioral Science To Make Better Drivers was published first on Pizza in Motion.